Check out my post on Edutopia!

A few weeks ago, a Writing Project colleague engaged a group of us in a conversation about how teachers might end the school year. This is typically an easy question. Most districts have traditions and rituals in place for ending the year, along with district assessments to measure academic growth. None of these typical ways to end will be in place this year, so this easy question morphed into several challenging questions:

How can we help students find a meaningful conclusion to this strange school year? What important elements of ways we typically wrap the school year can we preserve in a virtual assignment?

I started thinking about the ways I typically wrapped up the learning for the year in my own classroom. For many years, I asked students to write me a letter (or any format they wished to create) reflecting on their growth as a reader and as a writer. I also asked them to create an “other” category to reflect on something else they felt they learned through the year. I wanted to hear what they thought about their own learning: successes, struggles, next goals, and personal reflections to make sense out of everything.

The “other” category often spoke to my teacher heart, and that section was the reason a letter ended up in my “forever” file. One of my last years of teaching, a boy wrote about how he learned he was not such a misfit after all. One of my early years of teaching, a girl wrote about how journaling helped her process and figure out a way to let go of an abusive boyfriend. This was the learning that I worry virtual classrooms cannot foster, at least not as well.

The teenage years are a critical time for social interaction. Robbed of face-to-face connections, teens are not developing their identities through normal social interactions, rituals, and traditions.

Thinking about these issues of isolation, I brainstormed a list of key elements of an end-of-year activity. I landed on two: reflection and choice.

Asking students to process and reflect on the realities of this school year might help them make some sense of their world. Having worked with teenagers for more than 30 years, I also know meaningful reflection is not something all teens do naturally. Choice is always important for teens, but distance learning elevates choice to a critical component to me. Now I just needed to combine reflection with some choices for self-expression to create an answer to the question of how to wrap up this year.

First, students would need to review our common definition of reflective writing. For this blog, we will use this one: Communicating your thoughts and feelings about experiences, opinions, events, or ideas; exploring your learning and gaining self-knowledge/insight.

Next, I would tap into prior knowledge by asking groups of students to post what they remembered from mentor texts we had read during the school year. Groups could collaborate on Padlet, meet in small breakout rooms on Zoom, or use whatever virtual platforms your district provides.

Some of the mentor texts I have used for reflective writing include “Fish Cheeks” by Amy Tan and “Us and Them” by David Sedaris for middle schoolers; House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros and Night by Elie Wiesel for students in 9th/10th grade; and selections from Walden by Henry David Thoreau and from Citizen by Claudia Rankine for students in 11th /12th grade. Students could dip back into key parts, such as the last segment of “Fish Cheeks,” to review what they had learned about reflective writing early in the year.

Because video is a key component of distance learning, the mentor text I would use for this lesson would be in video format. I recommend an old favorite: the Favorite Poem Project. There are many, many potential mentor texts on this site, but the one I have used with success is John Doherty, a construction worker from Boston, who explains why Whitman’s Song of Myself is his favorite poem. I would ask students to do what we typically do when we look at a mentor text for craft.

Noticing craft: What do you notice about this video? What resonates with you as a viewer and listener? What seems to be important for this mode of expression?

Listen.

Listen again, and jot notes.

Then as a class, we would build a list of qualities we noticed in this mentor text, a list to help shape our idea of what reflective thinking/writing includes. Here is an example a class might shape from the video:

- Share a little background information.

- Reflect on your topic: How do you feel about it? What makes sense to you? What doesn’t? Why is it important to you?

- Draw conclusions or make implications: How is this important in a larger context, such as next year (or several years)? (Older students might use a specific critical lens.)

If there was enough time, I would ask them to listen a third time to see if they wanted to add anything to our list. Then we would discuss the list, and I would pose my typical questions: What would be easy about this kind of reflection? What would be challenging?

Working through a mentor text to create a list of qualities would be one full mini-lesson. If you want to extend this lesson, students could select another video on their own to “test” the class list of qualities. They could also create a Flipgrid to share a reflection on their own poem and give feedback to each other if you wanted to provide some practice.

For an end-of-year assignment, though, reflective writing (or a reflective video) would be part of a larger assignment. I decided the best way to provide students with options would be a choice board. Choice boards seem to be the perfect distance-learning tool, and I found some easy-to-use templates on helloteacherlady’s blog: helloteacherlady.com. Then I brainstormed ideas for activities at various difficulty levels.

I linked a sample board here.

All of the choices have components students would be familiar with from earlier in the school year. My goal is that each student will find a vehicle for self-expression and reflection no matter what activity he/she chooses to complete. There are so many potential adaptations for the choice boards, and the template is easy to revise however you wish.

After students completed the activities, another essential part would be to share and to provide responses to each other’s products. One way students could share would be to post their final product to a Padlet wall, such as this one. Then students could provide feedback to some of their peers with a little guidance if you wanted to provide it.

While no activity can substitute for finishing a school year with friends, maybe reflecting and sharing will help students make a little sense of their current reality. Maybe it could help us, too.

Ask any ELA teacher to tell you some of the main challenges of the job, and a likely answer is keeping up with responding to student writing. It’s a laborious task, yet we know it’s a significant part of helping student writers. In fact, no writer improves without two things: lots and lots of practice, and helpful feedback.

Yet a secondary teacher who has anywhere from 100 to 180 students cannot provide as much effective feedback as they would like to provide. So many of us turn to peer feedback to help.

From my experience, peer feedback works best when students are with writing partners/groups for a chunk of time. Building trust must happen before students can provide good feedback, and more importantly, before they will accept feedback from other students.

Just like any other structure, the success of peer feedback rests on clear expectations and modeling of both the “right” and “wrong” way. The first time I expect students to provide feedback in a school year, I like to ask volunteers to fishbowl an example. I pull the volunteers into the hall while I ask the remaining students to work with their groups to create descriptions of what they expect a good peer conference to look like. I work quickly with the volunteer group to create a brief example of a bad conference. Honestly, it usually goes beyond bad to truly terrible!

As you might guess, this fishbowl results in a lot of laughs, but it also creates an entry point to talk about negative behaviors. After the laughs subside, we debrief and create a list of all the bad behaviors and a class chart of what should happen instead.

Then it’s time to practice. Like with any other practice, I walk the room, listening in on groups and making notes of points and behaviors to highlight. Students love to be highlighted in positive ways, and I reinforce my expectations through these positive highlights – a win-win!

In addition to behavior expectations, I also use protocols to provide structure and language so all students can find success.

Here are a few of my favorite protocols.

Best Line and Three Questions: Peers find a “best line” in the piece, and they share why they chose this line in discussion. Then they ask three genuine questions. Students may need a mini-lesson on generating helpful questions, and all students will need you to model this protocol, maybe several times, before they will be able to do it well.

If students are not quite ready for Best Line, perhaps start with this sentence stem protocol: I noticed (positive) . . . , and as a reader, I would like . . . .

PQP – Praise, Question, Polish: This protocol is widely used, and you can find many versions online. This works well with older or more experienced students. Most teachers provide a few sentence stems for each of the three feedback categories, so I listed some below.

Praise: Identify the strengths of the piece.

- “My favorite part is … because …”

- “… was effective because …”

- “You were really clear about …”

- “As a reader, I particularly enjoyed …”

Question: Dig into both the structure and the content of the piece. Cross reference the writing with the assignment and/or rubric.

- “Could you help me to see … better?”

- “Would you consider adding (taking out, changing) … in order to …?”

- “What if you moved this word or phrase? (Provide thinking for the move.)

- “I’m not sure I understand this part clearly; (then provide specific question)”

Polish: Look at the “big picture” to consider the writing as a whole. What should the writer focus his/her attention on to add the final touches to the piece?

- Have you considered …?

- Could you add more to … in order to …?

- What do you want your readers to think, do, or believe when they are finished reading your piece?

- If you made this structural revision [define], your readers would ….

For younger students, use My Turn, Your Turn. You model a specific feedback statement, like a “best line” that includes figurative language, and then instruct all students to find a best line with figurative language. Be sure to model with academic language.

There are many, many protocols to help you guide students as they provide peer feedback, and in helping each other, they become critical readers and develop strong “read like a writer” skills. Done well, days spent providing peer feedback are powerful learning days!

Now that students have ideas, it’s time to flesh out the stories.

With any piece of writing, two parts are critical for students: ideas and organization. Both of these, known to many teachers as traits of writing, can be difficult for any writer. Who hasn’t labored over a first rough draft, trying hard to find a way to pull it together? Writing is hard work, so it’s no wonder students find ways to avoid it sometimes.

When you are ready for students to dig in and write a piece of fiction (or any other piece of writing), it’s important to think about what writers need. I know I need time – time to think, time to experiment, time to get feedback, time to re-examine mentor texts, time to rewrite, and time to read my work out loud.

That’s a lot of time, especially since teachers are constantly battling the clock.

The only way I know to provide students with enough time and support is to utilize a workshop structure in the classroom. If you need a quick overview on workshop structure, check out this blog post from Two Writing Teachers. Workshop provides students in-class time for all the critical parts writing, including time to confer with me and with peers, rather than setting the expectation that students will write outside of class time without support.

After spending some writing workshop time on thinking, drafting, and conferring, students are ready for narrowing their focus and “reading like a writer” again, but with a specific lens. To limit this activity, I ask students to read their mentor texts for the following: character, suspense, and conflict. High school students can handle working on all three, but for middle school students, I would suggest letting them choose one, or one at a time at least.

To provide some structure, I pose a few questions such as these:

- Character: What character trait is most important about the main character? How does the writer reveal it in the story? How do this character’s actions move the plot?

- Suspense: Where does the writer build tension in the story? How did he/she build this tension for the reader? Why does it work?

- Conflict: What is blocking the character from getting what s/he wants? Does this conflict escalate/complicate as the story progresses? Does this conflict come from outside and inside?

Students spend time working alone, reading and annotating. Then students meet with their writing group, or you can re-group students by the mentor text or element they chose to analyze.

All students work on the question “What did you learn about characterization, suspense, and/or conflict that you want to try in your writing?”

I think this is an important question on which to spend a little whole-class time debriefing. Students can benefit from hearing which techniques other writers prioritized and ways students discuss the elements of fiction. Clearly, students are developing their reading skills throughout this lesson series, and listening to what other students notice is a low stakes way of developing students’ knowledge of and ability to analyze text.

Armed with ideas and techniques, it’s back to writing time. Younger students may be adding on to their quickwrite, while more skilled or older students should be deep into their drafts.

Within a workshop schedule, time to write, confer, and revise continues for days. I try to have copies of mentor texts available around the room so students can get “professional” help without waiting for me.

Students are also always working on reading goals – always.

Our classroom expectation is this: If you are stuck during writing time, switch to reading. Of course, this was something I dedicated time to at the beginning of the school year, defining and modeling expectations, and even so, I would sometimes need to pull a student to have a behavior conference instead of a writing conference.

For students who come to class without their independent reading books, I always have plenty of books of all genres around the room. Sometimes, though, students do not want to dive into a new book, so I borrowed a wonderful strategy from my colleague Whitney Keeton. Whitney provides newspaper stories she thinks students might be interested in, and students are able to pick an article, read it, and put it back before they leave the classroom. Yes, sometimes a student simply wants to read how a favorite sports team fared the night before, but the student is still reading!

If I notice a student chooses to read rather than to write several days in a row, I make sure to confer with that student. It could be that the student prefers to write at home. Or it could be that the student is stuck and needs my help to move forward with the writing. Reluctant writers sometimes need short, specific writing goals for each day, so that might be worth posting each day. The best determiners of success are making sure students are interested in what they are writing and feel secure in the classroom community. If these two things are in place, I have successful writing workshop days!

Next, students use protocols to provide feedback to each other.

It’s that time of year — the dreaded preparation time for state assessments!

Over my career, many folks told me “Just don’t worry about it.” The reality for a classroom teacher is we have an obligation to our students, to their parents/guardians, and to the other stakeholders of our communities to do what we can to prepare students both academically and emotionally.

I am a parent and a community stakeholder, too, you see, and as such, I support measures for reducing the number of tests, I participate in writing and evaluating assessment questions, and I advocate for kids always. But if students will be tested, I will help them prepare.

Although most tests are a combination of reading and writing (and a few other topics), I am going to zoom in on writing for this post.

In recent years, as we approached review time, I would lead a book chat on the Divergent. Most of my students have read the series, but there were always a few who were not familiar with the story. Then students would line up and draw for their “faction,” an idea I stole from colleague Mindy Bishop years ago. Throughout test review time, usually two weeks, students sat with their factions, and each day, I presented the factions a challenge. Often students had to work individually on the task first, but I built in a collaborative element to each challenge. As a team, the factions scored points every day. (These were not grades or points for the gradebook.) Setting up the review in this way made it fun, and honestly, the students put more effort that usual into each task.

I recently heard from Mindy, and here’s her new spin on making assessment review fun: “I called it March MAP Madness. The kids were different college basketball teams from the tournament, and the different MAP prep activities scored them points for their teams. It was a huge hit with the kids. The championship team from each hour “won” a pizza lunch with me. They worked so hard to be the winner. I just love middle schoolers!”

To review for an on-demand writing assessment, I usually start with prompt analysis. If students cannot determine exactly what they are being asked to do, they cannot be successful. Some questions for prompt analysis include the following:

- What exactly is the prompt asking me to address in my answer?

- How many tasks are listed in the prompt?

- In what format should the answer be?

- How should I support my answer?

- How will my answer be evaluated?

- What process should I go through to accomplish this writing task?

While I model with a true prompt, one way to add fun is to ask students to devise silly, overly complicated prompts. Then they trade, do a prompt analysis, and share their results with the class. Be ready to laugh during the sharing part!

Next, I remind students not to skip prewriting. For most of us, the most difficult part of writing is simply gathering ideas and starting. Students can go into all-out panic mode just looking at the blank writing space! If you have been utilizing strategies such as Writing into the Day with quickwrites, your students only need a gentle reminder of tools in their toolbox, such as

- Quickwrite strategies for prewriting

- Protocols and reading strategies to approach prompts and articles

- Habits of mind to “enter the conversation” and to think about all perspectives

For tests, I think the most powerful strategy is the writing sprint. If students have practiced writing quickly from a word, picture, or simple prompt, they can utilize this strategy to get their thoughts started on the topic, and the simple act of stream-of-consciousness writing may calm their nerves.

As a way to practice without simply asking each student to write an essay, I often ask students to spend 10-20 quiet minutes writing ideas for answering a prompt, followed by time to share and discuss. Then students collaborate on an outline or draft, depending on time. Another approach is to ask everyone to write a quick draft, and then the group creates one draft, incorporating parts from everyone’s quick draft. The real benefit to these strategies is the conversation and negotiations the students have with each other as they work together.

Another activity I used many times was to provide students with student essays I had saved from previous years. Students highlighted parts they felt were successful in one color and unsuccessful in another color. Then they wrote feedback based on the checklist and/or rubric that would be used for the assessment. Usually the students were more critical than I was when I provided feedback!

If you need practice prompts, I have written two Missouri examples and linked them here:

http://tinyurl.com/EOC-sample-2019

https://tinyurl.com/SampleMAP2019

The MAP prompt is argumentative. (In Missouri, the EOC is a high school assessment, and the MAP is a middle school assessment.)

An important point to note is that some students need strategies for calming anxiety even after you have provided them with all they need to be successful. I found that having a conference to talk through the strategies students might use to calm the anxiety was worthwhile. It didn’t take away the anxiety, but the students knew I supported them and would be pulling for them on test day, and that’s worth something.

Want more ideas? See this work from the Plymouth Writing Project!

Good luck to everyone, teachers and students alike!

Follow my blog with Bloglovin

“It must be a piece of writing which, even if someone else reads it, doesn’t send any ripples back to you. It is like writing something and putting it in a bottle in the sea. . . . Freewritings help you by providing no feedback at all. ” Peter Elbow, 1973

“A quickwrite is a first draft response to a short piece of writing . . . . This is writing to find writing, but using someone else’s words to stimulate their thinking.” Linda Rief, 2018

Now comes the fun part – gathering ideas for writing!

Every writer can struggle to get started. Sometimes our commitments demand all of our attention. Sometimes our worries crowd out every other idea or thought. For many of us, our inner critic smashes down every inkling of an idea before it blossoms.

If all writers struggle, how does a teacher get a classroom full of students to write at the same time ? Quickwriting!

I first learned of this concept from Peter Elbow’s work. I was a new teacher at the time, and Elbow’s “freewriting” not only made sense for use with my students, but also helped me with my own writing through college. Freewriting as Elbow defines it is writing without stopping for a designated length of time. Then the writer chooses an idea from the freewriting and writes again. The goal is to keep going no matter what, even if you repeat a word or phrase over and over until a new idea comes.

In recent years, I’ve heard educators use terms such as “writing sprints” or “quickwrites.” Writing sprints increased in popularity alongside NaNoWiMo’s climb into the education world, and writers can even join a writing community of sprinters through Twitter ( See @NaNoWordSprints )Linda Rief uses the term quickwrite to combine mentor text models with writing ideas quickly as she described in her book The Quickwrite Handbook: 100 Mentor Texts to Jumpstart Your Students’ Thinking and Writing. Lots of educators, including me, use the term “quickwrite” to refer to a variation of freewriting and writing sprints.

All variations of a quickwrite have a few key qualities in common. They all

- Increase the amount writing in the classroom

- Help the writer focus on ideas without critique, either by an inner voice or the teacher

- Increase fluency over time

- Help writers of all ages find success, even enjoyment, in writing

- Utilize little class time

- Provide starting points for writing conferences

For our flash fiction unit, I used a variation that focuses the writer on brainstorming for a particular writing task. Although I altered the quickwrite prompt each year, here is an example:

Choose one of the following settings (or one of your own) and build the picture by focusing on imagery: What do you see? hear? smell? feel? taste?

- a real or imagined classroom

- night time in a woods (or city!)

- a childhood bedroom

- distant relative’s house

- an abandoned car on an embankment of a stream

- a setting of your choosing

My classroom routine for quickwrites looks like this:

- After I share the prompt and students have written the date in the quickwrites section of their notebook, students have a couple of quiet minutes for thinking. Then everyone, including me, writes for three minutes without stopping. I volley between writing and “kidwatching” to notice who might be struggling or to note someone to give a shout out to for their work.

- I quietly tell students when they have 30 seconds remaining. At the end of 30 seconds, I ask students to stop without finishing the sentence they are working on. If they know they want to come back to this piece, they can put ellipses.

- Everyone tallies their word count and writes it in the margin next to today’s quickwrite. I ask students to give me a thumbs up if their word count is at least 5 more words than their previous word count, a “thumbs to the side” if their word count is plus or minus 5 words, and a thumbs down if their word count is 5 or more fewer words than their previous word count. I make it clear that everyone is working on fluency at his or her own pace.

- Depending upon the goals for the day’s lesson, students might do a two-minute share with a shoulder partner, a few whole-group show of hands for who wrote to which choice, or a whole-group workshop session if a writer wanted to share his or her piece to get advice for next steps.

This routine is something I introduced every year, no matter which grade level I was teaching that year, in the first few days of school, and the classes practiced with high-engagement prompts until everyone knew the routine.

Yes, there were usually students who tried to avoid writing by writing “I don’t know what to write” over and over for the full three minutes, but that often stopped without my intervention. Students quickly realized how boring it was to write the same thing over and over, or they realized all writing was celebrated and none of it was perfect. If we were a week into the routine and the avoidance behaviors were still in place, it was time for a one-on-one conference to find out why and to do what I could to take away the student’s fear of writing.

For this assignment, I often chose a whole-group show of hands to get a sense of which settings appealed to each class, and then students shared with a writing partner. The partner’s job was to ask questions so the writer could continue to think about how the setting could be developed. We spent about 10 minutes of partner time, so this lesson was not a whole class period.

Next, students go back to a mentor text to read like a writer with a purpose.

A few years ago, my best friend Penny gave me Year of Yes: How to Dance It Out, Stand in the Sun and Be Your Own Person by Shonda Rhimes. Penny and I have been faithful followers of Grey’s Anatomy since it first aired, so she knew I would enjoy learning a bit of Shonda’s story.

The book details a year in Shonda’s life that stems from a discussion with her oldest sister at Thanksgiving in 2013, a discussion that centers on one statement:

“You never say yes to anything.”

Shonda describes how this statement created a pivotal moment in her life. The statement sticks with her until it wakes her up in the middle of the night several weeks later.

What follows is an inner monologue in which Shonda reveals her introverted nature, and as I was reading it, I was struck by how her words could have flowed from many students in my classroom that year. She has a revelation at the end of the monologue, and admits she is unhappy, even though she doesn’t feel she is “allowed” to be unhappy. This was another feeling I knew several students in my class held inside. As the title suggests, she commits to saying yes to as much as possible for an entire year to address her sister’s statement.

I decided to use this story as an after-holiday-break quickwrite. I shared some of the information in story form, and I read a couple of key pieces out loud, making sure to pick classroom-appropriate sections. Then I asked the students to reflect on what they could “say yes” to in their lives to help them reach a goal or generate more happiness. We all wrote for three minutes, and then for another three minutes, since no one was ready to stop when the usual length of time was up.

A few students were willing to share out loud, but most said their writing was too personal, and I respected that. Many said how much they enjoyed writing this quickwrite, and a few even said they were going to add more later. I transitioned to a discussion on stream-of-consciousness as a stylistic choice, and we had a fun first day back from break.

What struck me most about this experience was the way students kept bringing it up over the next few weeks. Some would come up to me in the hall to say they had been “saying yes” more often. Other said they told their parents about the writing and their parents offered to help them reach their goals. One girl asked if she could meet with me in private, and she shared her realization that she had not been very kind to a few other girls in the class because she felt inferior to them without cause. My goal had been to ease into a new semester with something I thought students might enjoy, and I had not anticipated the depth of their response to the assignment. I vowed to weave in more reflective quickwrites.

This kind of reflective journaling is not new, but some of the research about it is. In a recent New York Times article “What’s All This About Journaling?” noted the resurgence of reflective writing:

Once the domain of teenage girls and the literati, journaling has become a hallmark of the so-called self-care movement, right up there with meditation. And for good reason: Scientific studies have shown it to be essentially a panacea for modern life. There are the obvious benefits, like a boost in mindfulness, memory and communication skills. But studies have also found that writing in a journal can lead to better sleep, a stronger immune system, more self-confidence and a higher I.Q.

With all of these benefits and the current focus on trauma-informed teaching, reflective journaling is worth fitting into your curriculum if you have the option. I used my students’ positive reactions as my motivation to keep this as a first-day-back-from-break activity from that year on, and now I’m sharing it with you. Enjoy, and Happy New Year!

A few years ago, I served as Penny Kittle’s driver.

Yes, you read that sentence correctly.

No, I am not an Uber driver, nor am I particularly good driver. But Penny was in town, and she needed someone reliable to drive her from the hotel to the workshop venue for the two days she was presenting. To this day, I have no idea how this task fell to me, but I said yes.

Saying yes meant I had PENNY KITTLE trapped in a small space with no one but me to talk to! I utilized every minute of that time while trying to not overwhelm her with questions. (I considered asking her if I could tape our conversation, but I thought that might be going a bit too far.) She was kind and gracious, which made me appreciate her even more.

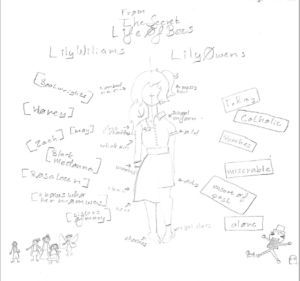

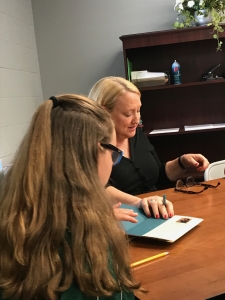

Serving as her driver meant I could attend the workshop, too. One of the many ideas Penny shared was an activity in which she sketched and annotated her thoughts in response to this question:

Have you ever had a moment when you felt two parts of who you are or who you want to be or who others expect you to be at war inside of you? Where you feel split in two but also whole all at once?

See the activity here.

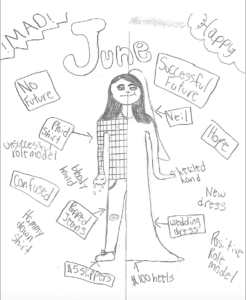

A couple of weeks later, my students finished book clubs, and I decided to try an adaptation of Penny’s idea. I asked students to think about how characters in their books changed from the beginning to the end of their stories. I asked them to think about what kind of changes were significant and notable versus changes that were insignificant, and I asked them to provide a sketch that revealed “before and after” attributes and details.

I wanted to see where students were in their understanding of character development, and I liked the idea of providing a low stakes, creative method for them to show me. I also decided to give students individual time to create their sketches, which gave them some space from their book club partners. I learned over the years that sometimes even the best groups need a little time to think away from each other.

When they finished, I asked them to meet in their book club groups to share their drawings and to discuss how they determined what they put on their sketches. As they talked, I captured some of their thoughts and ideas on my clipboard. These would be the ideas we would discuss.

I did not have my students dig in as deeply as Penny’s example shows, but I liked the results, and I attached a few for The Secret Life of Bees throughout this post. I quickly determined which students needed some conversation with me the following day, and then we had a strong whole-group discussion about the various ways students noticed important changes in their characters. The discussion was strong because all of the ideas came from the students — not from me, not from a list of pre-determined notes, not from a teacher’s guide.

What you cannot see, though, are the animated conversations that took place as students shared their thinking processes and their sketches. All of that joy and excitement prompted me to put everyone’s sketches on my bulletin board after school that day. The next day, students vied for space near the bulletin board. They were reading, commenting, asking questions to each other, etc. — exactly what every literacy teacher hopes to see students doing in response to books.

Thank you, Penny Kittle.

I was introduced to the concept of invitational groups when Ellin Keene first worked with our middle school ELA team. Our school had completed a book study of Mosaic of Thought, but it wasn’t until Ellin led a demonstration lesson in a colleague’s classroom that I started to understand the power of the invitational group. While Mosaic of Thought focuses on reading, the invitational group works just as well with writing, too. See below for a summary.

I started invitational groups as voluntary groups in my classroom: I would ask anyone who wanted to see me demonstrate a concept such as writing with imagery or thinking aloud about suspense in a text to join me in a certain location in the classroom. All the other students were writing or reading independently, or sometimes students were working with writing partners on giving feedback. After students became comfortable with the structure, I added the specific invitations to our routine.

While nothing can take the place of one-on-one conferencing, utilizing invitational groups helps solve a bit of the time issue, since the teacher can work with several students at once. Other students move at their pace, too, without being forced to spend time reviewing concepts they already understand, as often happens in whole-group mini-lessons.

Surprisingly, after invitational groups became a routine in my classroom, students who seemed secure with a concept sometimes self-selected into an invitational group. We all know students who are skilled at pretending they “get it” when in fact, they may be confused. Because this structure removes the stigma of “extra help,” students felt comfortable dipping into a group as needed.

Definition

Invitational groups are small groups of students who have shared needs for intensive instruction or discussion. Students are invited to participate in an invitational group so the teacher can reinforce or extend a concept discussed in whole-group instruction. (Students can also join voluntarily.) This is an opportunity to practice a skill with teacher support. Students have an opportunity to observe the teacher model in a more controlled, focused setting.

Setting up the Mini-lesson

Call students to a table or a close setting. Plan instruction to address a clearly identified need for each child in the group, such as reviewing a strategy, explaining a challenging writing convention, working on literary technique such as foreshadowing, etc. Establish routines and protocols to prohibit interruptions from other students. During reflection time, students who have participated in an invitational group can be invited to demonstrate what they have learned.

Frequency/Time Limits

Invitational groups are short, focused, and active. Invitational groups should be used as necessary and should rarely exceed fifteen minutes. Invitational groups are not static – the same group of children may meet one to three times to focus on an area of need; then they disband.

Adapted from Keene, Ellin Oliver, and Susan Zimmermann. Mosaic of Thought. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2007.