Ask any ELA teacher to tell you some of the main challenges of the job, and a likely answer is keeping up with responding to student writing. It’s a laborious task, yet we know it’s a significant part of helping student writers. In fact, no writer improves without two things: lots and lots of practice, and helpful feedback.

Yet a secondary teacher who has anywhere from 100 to 180 students cannot provide as much effective feedback as they would like to provide. So many of us turn to peer feedback to help.

From my experience, peer feedback works best when students are with writing partners/groups for a chunk of time. Building trust must happen before students can provide good feedback, and more importantly, before they will accept feedback from other students.

Just like any other structure, the success of peer feedback rests on clear expectations and modeling of both the “right” and “wrong” way. The first time I expect students to provide feedback in a school year, I like to ask volunteers to fishbowl an example. I pull the volunteers into the hall while I ask the remaining students to work with their groups to create descriptions of what they expect a good peer conference to look like. I work quickly with the volunteer group to create a brief example of a bad conference. Honestly, it usually goes beyond bad to truly terrible!

As you might guess, this fishbowl results in a lot of laughs, but it also creates an entry point to talk about negative behaviors. After the laughs subside, we debrief and create a list of all the bad behaviors and a class chart of what should happen instead.

Then it’s time to practice. Like with any other practice, I walk the room, listening in on groups and making notes of points and behaviors to highlight. Students love to be highlighted in positive ways, and I reinforce my expectations through these positive highlights – a win-win!

In addition to behavior expectations, I also use protocols to provide structure and language so all students can find success.

Here are a few of my favorite protocols.

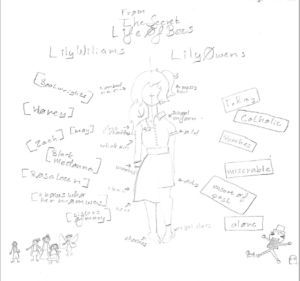

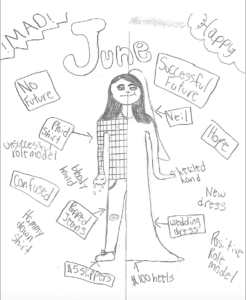

Best Line and Three Questions: Peers find a “best line” in the piece, and they share why they chose this line in discussion. Then they ask three genuine questions. Students may need a mini-lesson on generating helpful questions, and all students will need you to model this protocol, maybe several times, before they will be able to do it well.

If students are not quite ready for Best Line, perhaps start with this sentence stem protocol: I noticed (positive) . . . , and as a reader, I would like . . . .

PQP – Praise, Question, Polish: This protocol is widely used, and you can find many versions online. This works well with older or more experienced students. Most teachers provide a few sentence stems for each of the three feedback categories, so I listed some below.

Praise: Identify the strengths of the piece.

- “My favorite part is … because …”

- “… was effective because …”

- “You were really clear about …”

- “As a reader, I particularly enjoyed …”

Question: Dig into both the structure and the content of the piece. Cross reference the writing with the assignment and/or rubric.

- “Could you help me to see … better?”

- “Would you consider adding (taking out, changing) … in order to …?”

- “What if you moved this word or phrase? (Provide thinking for the move.)

- “I’m not sure I understand this part clearly; (then provide specific question)”

Polish: Look at the “big picture” to consider the writing as a whole. What should the writer focus his/her attention on to add the final touches to the piece?

- Have you considered …?

- Could you add more to … in order to …?

- What do you want your readers to think, do, or believe when they are finished reading your piece?

- If you made this structural revision [define], your readers would ….

For younger students, use My Turn, Your Turn. You model a specific feedback statement, like a “best line” that includes figurative language, and then instruct all students to find a best line with figurative language. Be sure to model with academic language.

There are many, many protocols to help you guide students as they provide peer feedback, and in helping each other, they become critical readers and develop strong “read like a writer” skills. Done well, days spent providing peer feedback are powerful learning days!