Now that students have ideas, it’s time to flesh out the stories.

With any piece of writing, two parts are critical for students: ideas and organization. Both of these, known to many teachers as traits of writing, can be difficult for any writer. Who hasn’t labored over a first rough draft, trying hard to find a way to pull it together? Writing is hard work, so it’s no wonder students find ways to avoid it sometimes.

When you are ready for students to dig in and write a piece of fiction (or any other piece of writing), it’s important to think about what writers need. I know I need time – time to think, time to experiment, time to get feedback, time to re-examine mentor texts, time to rewrite, and time to read my work out loud.

That’s a lot of time, especially since teachers are constantly battling the clock.

The only way I know to provide students with enough time and support is to utilize a workshop structure in the classroom. If you need a quick overview on workshop structure, check out this blog post from Two Writing Teachers. Workshop provides students in-class time for all the critical parts writing, including time to confer with me and with peers, rather than setting the expectation that students will write outside of class time without support.

After spending some writing workshop time on thinking, drafting, and conferring, students are ready for narrowing their focus and “reading like a writer” again, but with a specific lens. To limit this activity, I ask students to read their mentor texts for the following: character, suspense, and conflict. High school students can handle working on all three, but for middle school students, I would suggest letting them choose one, or one at a time at least.

To provide some structure, I pose a few questions such as these:

- Character: What character trait is most important about the main character? How does the writer reveal it in the story? How do this character’s actions move the plot?

- Suspense: Where does the writer build tension in the story? How did he/she build this tension for the reader? Why does it work?

- Conflict: What is blocking the character from getting what s/he wants? Does this conflict escalate/complicate as the story progresses? Does this conflict come from outside and inside?

Students spend time working alone, reading and annotating. Then students meet with their writing group, or you can re-group students by the mentor text or element they chose to analyze.

All students work on the question “What did you learn about characterization, suspense, and/or conflict that you want to try in your writing?”

I think this is an important question on which to spend a little whole-class time debriefing. Students can benefit from hearing which techniques other writers prioritized and ways students discuss the elements of fiction. Clearly, students are developing their reading skills throughout this lesson series, and listening to what other students notice is a low stakes way of developing students’ knowledge of and ability to analyze text.

Armed with ideas and techniques, it’s back to writing time. Younger students may be adding on to their quickwrite, while more skilled or older students should be deep into their drafts.

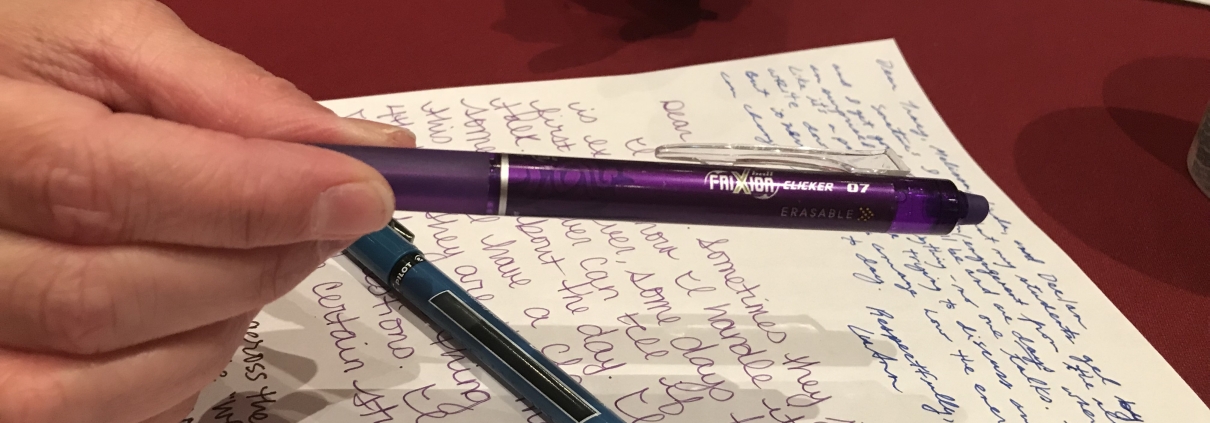

Within a workshop schedule, time to write, confer, and revise continues for days. I try to have copies of mentor texts available around the room so students can get “professional” help without waiting for me.

Students are also always working on reading goals – always.

Our classroom expectation is this: If you are stuck during writing time, switch to reading. Of course, this was something I dedicated time to at the beginning of the school year, defining and modeling expectations, and even so, I would sometimes need to pull a student to have a behavior conference instead of a writing conference.

For students who come to class without their independent reading books, I always have plenty of books of all genres around the room. Sometimes, though, students do not want to dive into a new book, so I borrowed a wonderful strategy from my colleague Whitney Keeton. Whitney provides newspaper stories she thinks students might be interested in, and students are able to pick an article, read it, and put it back before they leave the classroom. Yes, sometimes a student simply wants to read how a favorite sports team fared the night before, but the student is still reading!

If I notice a student chooses to read rather than to write several days in a row, I make sure to confer with that student. It could be that the student prefers to write at home. Or it could be that the student is stuck and needs my help to move forward with the writing. Reluctant writers sometimes need short, specific writing goals for each day, so that might be worth posting each day. The best determiners of success are making sure students are interested in what they are writing and feel secure in the classroom community. If these two things are in place, I have successful writing workshop days!

Next, students use protocols to provide feedback to each other.

Since each person in a table group read a different selection, students regrouped all around the room with other students who read the same text. I provided time for students to discuss and to ask questions, and then I directed students to “read like a writer with a focus ” while I listened in and guided groups as needed.

Since each person in a table group read a different selection, students regrouped all around the room with other students who read the same text. I provided time for students to discuss and to ask questions, and then I directed students to “read like a writer with a focus ” while I listened in and guided groups as needed.